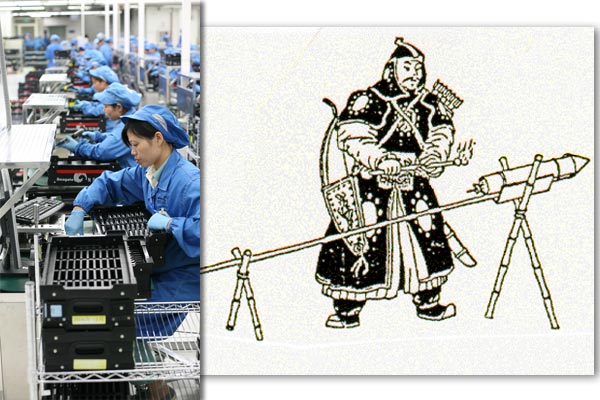

A couple of anecdotes to remember before accepting the conventional wisdom that all China is good for is mass-producing (or copying) non-Chinese tech products (i.e. iPhones):

From Seymour Hersh’s recent New Yorker piece examining the hype of cyber-warfare:

A few weeks after Barack Obama’s election, the Chinese began flooding a group of communications links known to be monitored by the N.S.A. with a barrage of intercepts, two Bush Administration national-security officials and the former senior intelligence official told me. The intercepts included details of planned American naval movements. The Chinese were apparently showing the U.S. their hand.

“The N.S.A. would ask, ‘Can the Chinese be that good?’ †the former official told me. “My response was that they only invented gunpowder in the tenth century and built the bomb in 1965. I’d say, ‘Can you read Chinese?’ We don’t even know the Chinese pictograph for ‘Happy hour.’ â€

And today’s New York Times, on a Chinese research center building a supercomputer that outclocks the current one by 40 percent.

Modern supercomputers are built by combining thousands of small computer servers and using software to turn them into a single entity. In that sense, any organization with enough money and expertise can buy what amount to off-the-shelf components and create a fast machine.

The Chinese system follows that model by linking thousands upon thousands of chips made by the American companies Intel and Nvidia. But the secret sauce behind the system — and the technological achievement — is the interconnect, or networking technology, developed by Chinese researchers that shuttles data back and forth across the smaller computers at breakneck rates, Mr. Dongarra said.

“That technology was built by them,†Mr. Dongarra said. “They are taking supercomputing very seriously and making a deep commitment.â€

The Chinese interconnect can handle data at about twice the speed of a common interconnect called InfiniBand used in many supercomputers.