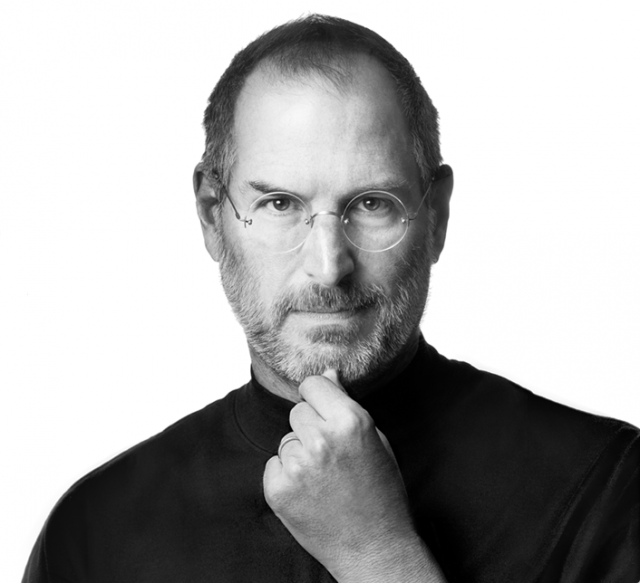

Rep. Lamar Smith, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee and SOPA sponsor

Update (1/22/2012): SOPA was indefinitely postponed by Rep. Lamar Smith on Friday (PIPA is likewise stalled). Rep. Smith also has another Internet rights bill on deck though: the The Protecting Children from Internet Pornographers Act of 2011, which mandates that Internet services store customer data for up to 18 months to make it easier for law enforcement to investigate them for child porn trafficking. This proposed bill is discussed in the latter half of this post, including how its level of support is similar (and different) than SOPA’s.

H.R. 1981 has made it farther than SOPA did. It made it out of the Judiciary Committee (which is chaired by Rep. Lamar Smith and also handled SOPA) with a 19-10 vote in July of last year and is placed on the Union Calendar. Compare HR.1981’s progress compared to SOPA’s). H.R. 1981 has 39 cosponsors, compared to SOPA’s original 31. Read the text of HR 1981.

One thing I’ve learned from the whole SOPA affair is how obscure our lawmaking process is even in this digital age. The SOPA Opera site I put up doesn’t do anything but display publicly available information: which legislators support/oppose SOPA and why. But it still got a strong reaction from users, possibly because they misunderstand our government’s general grasp of technology issues.

The most common refrain I saw was: “I cannot believe that Rep/Senator [insert name] is for SOPA! [insert optional expletive].” In particular, “Al Franken” was a frequently invoked name because his fervent advocacy on net neutrality seemed to make the Minnesota senator, in many of his supporters’ opinions, an obvious enemy of SOPA. In fact, one emailer accused me of being out to slander Franken, even though the official record shows that Franken has spoken strongly for PROTECT-IP (the Senate version of SOPA) and even co-sponsored it.

So there’s been a fair amount of confusion as to what mindset is responsible for SOPA. Since party lines can’t be used to determine the rightness/wrongess of SOPA, fingers have been pointed at the money trail: SOPA’s proponents reportedly receive far more money from media/entertainment-affiliated donors than they do from the tech industry. The opposite trend exists for the opponents.

It’s impossible of course to know exactly what’s in the our legislators’ minds. But a key moment during the Nov. 16 House Judiciary hearing on SOPA suggest that their opinions may be rooted less in malice/greed (if you’re of the anti-SOPA persuasion) than in something far more prosaic: their level of technological comprehension.

You can watch the entire, incredibly-inconvenient-to-access webcast at the House Judiciary’s hearing page. I’ve excerpted a specific clip in which Rep. Tom Marino (R-PA) is asking Katherine Oyama (Google’s copyright lawyer) about why Google can stop child porn but not online piracy:

REP. MARINO: I want to thank Google for what it did for child pornography – getting it off the website. I was a prosecutor for 18 years and I find it commendable and I put those people away. So if you can do that with child pornography, why can you not do it [with] these rogue websites [The Pirate Bay, et al.]? Why not hire some whiz kids out of college to come in and monitor this and work for the company to take these off?

My daughter who is 16 and my son who is 12, we love to get on the Internet and we download music and we pay for it. And I get to a site and I say this is a new one, this is good, we can get some music here. And my daughter says Dad, don’t go near that one. It’s illegal, it’s free, and given the fact that you’re on Judiciary, I don’t think you should be doing that…Maybe we need to hire her [laugh]…but, why not?

OYAMA: The two problems are similar in that they’re both very serious problems they’re both things that we all should be working to fighting against. But they’re very different in how you go about combatting it. So for child porn, we are able to design a machine that is able to detect child porn. You can detect certain colors that would show up in pornography, you can detect flesh tones. You can have manual review, where someone would look at the content and they would say this is child porn and this shouldn’t appear.

We can’t do that for copyright just on our own. Because any video, any clip of content, it’s going to appear to the user to be the same thing. So you need to know from the rights holder…have you licensed it, have you authorized it, or is this infringement?”

REP. MARINO: I only have a limited amount of time here and I appreciate your answer. But we have the technology, Google has the technology, we have the brainpower in this country, we certainly can figure it out.

The subject of child pornography is so awful that it’s little wonder that no one really thinks about how it’s actually detected and stopped. As it turns out, it’s not at all complicated.

When I was a college reporter, I had the idea to drive down to the county district attorney’s office and go through all the search warrants. Search warrants become part of the public record, but district attorneys can seal them if police worry that details in an affidavit or search warrant would jeopardize an investigation. I wanted to count how many times this was done at the county DA, because some major cases had been sealed for months. And I wondered if the DA was too overzealous in keeping private what should be the people’s business.

But there were plenty of big cases among the unsealed warrants. I went to college in a small town but there was a bizarre, seemingly constant stream of students being charged with child porn possession. Either college students were becoming particularly perverse or the campus police happened to be crack cyber-sleuths in rooting out the purveyors.

I don’t know about the former, but I learned that the police were not particularly skilled at hacking, based on their notes in the search warrants. In fact, finding the suspects was comically easy because of the unique setup of our college network. Everyone in the dorms had an ethernet hookup but there was no Google, Napster or BitTorrent at the time. So one of the students built a search engine that allowed any student to search the shared files of every other student. And since Windows apparently made this file sharing a default (and at the time, 90+ percent of students’ computers were PCs), the student population had inadvertent access to a huge breadth of files, including MP3s and copied movies and even homework papers.

So to find out if anyone had child porn, the police could just log onto the search engine and type in the appropriate search terms. But the police didn’t even have to do this. Other students would stumble upon someone’s porn collection (you had the option of exploring anyone’s entire shared folder, not just files that came up on the search) and report it. The filenames were all the sickening indication needed to suspect someone of possession.

Google’s Oyama alludes to more technically sophisticated ways of detecting it, but the concept is just as simple as it was at my college: no matter how it’s found, child pornography is easy to categorize as child porn because of its visual characteristics, whether it’s the filename or the images itself. In fact, it’s not even necessary for a human to view a suspected file to know (within a high mathematical probability) that it contains the purported illegal content.

If you’ve ever used Shazam or any of the other song-recognition services, you’ve put this concept into practice. When you hold up a phone to identify a song playing over the bar’s speakers, it’s not as if your phone dials up one of Shazam’s resident music experts who then responds with her guess of the song. The Shazam app looks for certain high points (as well as their spacing, i.e. the song’s rhythm) to generate a “fingerprint” of the song, and then compares it against Shazam’s master database of song “fingerprints”.

No human actually has to “listen” to the song. This is not a new technological concept; it’s as old as, well, the fingerprint database used by law enforcement.

So what Rep. Marino essentially wants is for Google to build a Shazam-like service that doesn’t just identify a song by “listening” to it, but also determines if whoever playing that song has the legal right to do so. Thus, this anti-pirate-Shazam would have to determine from the musical signature of a song such things as whether it came from an iTunes or Amazon MP3 or a CD. And not only that, it would have to determine whether or not the MP3 or CD is a legal or illegal copy.

In a more physical sense, this is like detecting a machine that can determine from a photograph of your handbag whether it’s a cheap knockoff and whether or not you actually own that bag – as opposed to having stolen it, or having bought it from someone who did steal it.

I’m not a particularly skilled engineer but I can’t fathom how this would be done and neither can Google, apparently. But Rep. Marino and at least a few others on the House Judiciary committee have more faith in Google’s technical prowess and they don’t believe that Google is doing enough.

And frankly, I can’t blame them.

From their apparently non-technical vantage point, what they see is that Google is an amazing company who seems to have no limit in its capabilities. It can instantly scour billions of webpages. It can plot in seconds the driving route from Des Moines ot Oaxaca, Mexico. And at some point, might even make a car that drives that route all by itself.

And Google has demonstrated the power to stop evil acts, because it has effectively prevented the spread of child porn in its search engine and other networks. Child porn is a terrible evil; software/media piracy less so. It stands to reason – in a non-technical person’s thinking – that anyone who can stop a great evil must surely be able to stop a lesser evil.

And so, to continue this line of reasoning, if Google doesn’t stop a lesser evil such as illegal MP3 distribution, then it must be because it doesn’t care enough. Or, as some House members noted, Google is loathe to take action because it makes money off of sites that trade in ill-gotten intellectual property.

So you can see how one’s position on SOPA may be inspired not as much out of devotion to an industry but more from a particular (or lack thereof) understanding of the technological tradeoffs and hurdles.

Rep. Marino et. all sees this as something within the realm of technological possibility for Google’s wizards, if only they had some legal incentive. Google and other SOPA opponents see that the problem that SOPA ostensibly tackles is not one that can be solved with any amount of technological expertise. Thus, each side can be as anti-online-piracy/pro-intellectual-property as the other and yet fight fiercely over SOPA.

Smith’s anti-child porn, database-building bill

Though SOPA has taken the spotlight, there is another Internet-related bill on the House Judiciary’s agenda. It’s H.R. 1981, a.k.a The Protecting Children from Internet Pornographers Act of 2011, which proposed a mandate that Internet sites keep track of their users IP information for up to 18 months, to make it easier to investigate Internet crimes – such as downloading child pornography.

H.R. 1981 was introduced by House Judiciary Chairman Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Tex.) who is, of course, the legislator who introduced SOPA. And like SOPA, the support for H.R. 1981 is non-partisan because child pornography is neither a Republican or Democratic cause.

And also like SOPA, the opposition to H.R. 1981 is along non-partisan lines. Among the most vocal opponents to the child porn bill is the Judiciary committee’s ranking member Rep. John Conyers (D-MI). Is it because he is in the pocket of the child porn lobby? No; Conyers argues that even though child porn is bad, H.R. 1981 relies on using technology in a way that is neither practical nor ethical. From CNET:

The bill is mislabeled,” said Rep. John Conyers of Michigan, the senior Democrat on the panel. “This is not protecting children from Internet pornography. It’s creating a database for everybody in this country for a lot of other purposes.”

Rep. Conyers apparently understands that just because a law purports to fight something as evil (and, of course, politically unpopular) as child pornography doesn’t mean that the law’s actual implementation will be sound.

So when the wrong-to-be-righted is online piracy – i.e. SOPA – what is Conyers’ stance? He is one of its most vocal supporters:

The Internet has regrettably become a cash-cow for the criminals and organized crime cartels who profit from digital piracy and counterfeit products. Millions of American jobs are at stake because of these crimes.

Is it because Conyers is in the pocket of big media? Or that he hates the First Amendment? That’s not an easily apparent conclusion judging from his past votes and legislative history.

It’s of course possible that Conyers takes this particular stance on SOPA because SOPA, all things considered, happens to be a practical and fair law in the way that H.R. 1981 isn’t.

But a more cynical viewpoint is that Conyer’s technological understanding for one bill does not apply to the other. Everyone has been screwed over at some point by a massive, faceless database so it’s easy to be fearful of online databases – in fact, the less you know about computers, the more concerned you’ll be of the misuse of databases.

The technological issues underlying SOPA are arguably far more complex, though, and it’s not clear – as evidenced by Rep. Marino’s line of questioning – that Congressmembers, whether they support or oppose SOPA, have a full understanding of them.

As it stands though, SOPA had 31 cosponsors at its heyday. H.R. 1981 has 39. It will be interesting to see if this bill by Rep. Smith will face any residual backlash after what happened with SOPA.