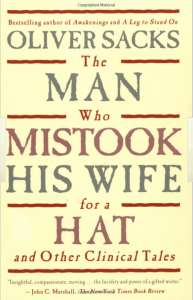

Last week, I bought a paperback version of Dr. Oliver Sacks’ “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” just because I liked the title, and it’s been the best purchase I’ve made in months and the first book I’ve read through in about a year. It’s a collection of clinical tales of abnormal neurology and psychology. The titular essay is about a man who had perfectly fine eyesight and taught music at a prestigious school, but had a massive defect in internal visualization, hence, seeing a hat (and trying to pick it up) where his wife’s head was.

In many ways, it’s a depressing glimpse to at how our personalities, mannerisms, even our “souls” are so dependent on the material of the brain. In one chapter, a man murders his daughter under the influence of PCP and is blissfully unaware of the tragedy, until a massive head injury blissfully causes him to relive the memory as his own personal hell. On the whole, some of the anecdotes are inspiring, illustrating how what is perceived as abnormality by our society can be the basis for artistic genius. In one chapter, he describes a man with Tourette’s Syndrome who, despite constant outbursts of profanity, is able to live not only a relatively normal life, but also one in which is music and athletic skills are enhanced by the spastic neurons in his brain. When Dr. Sacks gives him a drug to mitigate his Tourette’s, the man finds he’s clumsier, less inspired…and gives up the drug rather than live a dull “normal” life (he ends up compromising by taking the drug during the workday, and letting his “normal” self shine on the weekends).

The following story probably has been made into a Lifetime movie, but is pretty inspiring no matter how normal your neurological condition may be:

Madeline J. was admitted to St. Benedict’s Hospital near New York City in 1980, her sixtieth year, a congenitally blind woman with cerebral palsy, who had been looked after by her family at home throughout her life. Given this history…I expected to find her both retarded and regressed.

She was neither. Quite the contrary: she spoke freely, indeed eloquently, revealing herself to be a high-spirited woman of exceptional intelligence and literacy.

“You’ve read a tremendous amount,” I said. “You must be really at home with Braille.”

“No, I’m not,” she said. “All my reading has been done for me – by talking-books or other people. I can’t read Braille, not a single word. I can’t do anything with my hands – they are completely useless.”

She held them up, derisively. “Useless godforsaken lumps of dough – they don’t even feel part of me.“

I found this very startling. The hands are not usually affected by cerebral palsy…Miss J’s hands…her sensory capacities – as I now rapidly determined – were completely intact.

There was no impairment of elementary sensation, as such, but, in dramatic fashion, there was the profoundest impairment of perception. She could not identify – and she did not explore; there were no active ‘interogatory’ movements of her hands – they were, indeed, as inactive, as inert, as useless as “lumps of dough.”

Dr. Sacks then wonders if that Miss J’s hands are functionless because, being blind and tended to her whole life, she had never used them:

Had being ‘protected’, ‘looked after’, ‘babied’ since birth prevented her from the normal exploratory use of the hands which all infants learn in the first month of life? And if this was the case – it seemed far-fetched, but was the only hypothesis I could htink of – could she now, in her sixtieth year, acquire what she should have acquired in the first weeks and months of life?

Dr. Sacks devises a simple test of his hypothesis, to prod Miss J to use her hands out of necessity:

I thought of the infant as it reached for the breast. “Leave Madeleine her food, as if by accident, slightly out of reach on occasion,” I suggested to her nurses. “Don’t starve her, don’t tease her, but show less than your usual alacrity in feeding her.”

And one day it happened – what had never happened before: impatient, hungry, instead of waiting passively and patiently, she reached out an arm, groped, found a bagel, and took it to her mouth. This was the first use of her hands, her first manual act, in sixty years, and it marked her birth as a ‘motor individual’.

…

And then – this was within a month of her first recognitions – her attention, her appreciation, moved from objects to people…She started to model heads and figures, and within a year was locally famous as the Blind Sculptress of St. Benedict’s.

For me, for her, for all of us, this was a deeply moving, an amazing, almost a miraculous experience. Who would have dreamed that basic powers of perception, normally acquired in the first months of life, but failing to be acquired at this time, could be acquired in one’s sixtieth year? What wonderful possibilities of late learning, and learning for the handicapped, this opened up.

The rest of the chapter is as moving as this excerpt. It’s an old book, almost a classic as its first print was in 1970. If you’re like me and always far behind on your reading list, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat is worth picking up for its timeless scientific insight and wonder.