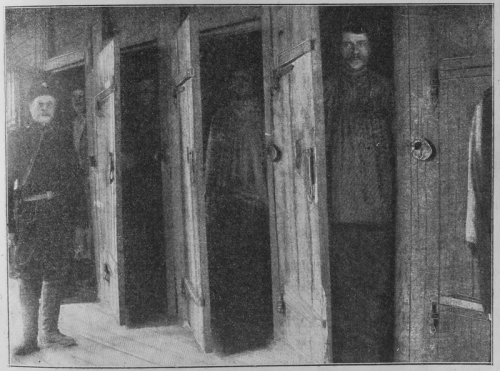

Punishment Cells. From: Page 257 of part II of Vlas Mikhailovich Doroshevich «Sakhalin (Katorga)», Moscow. Sytin publisher, 1905.

Thanks to longform.org for spotlighting another thought-provoking piece by Dr. Atul Gawande in the New Yorker. The tag line is: Hellhole: The United States holds tens of thousands of inmates in long-term solitary confinement. Is this torture?

Dr. Gawande’s reporting builds a strong case for “Yes.” Some interesting bullet points:

- America holds at least 25,000 inmates in solitary confinement in Supermax prisons

- More than a century ago, the U.S. Supreme Court considered banning solitary confinement

- A 2003 analysis of Arizona, Illinois, and Minnesota found that levels of inmate-on-inmate violence were unchanged after their supermax prisons opened

- The state of Maine has more inmates in long-term solitary than does all of England

Supermax prisons and the long-term isolation of large numbers of inmates, Dr. Gawande notes, is only a decades-old concept in the American prison system. However, in the 1890 SCOTUS case, Medley vs. U.S., the court takes note of a solitary confinement system in Philadelphia back in 1787. The conditions and consequences, noted more than two centuries ago, aren’t much different than what Dr. Gawande describes today:

The peculiarities of this system were the complete isolation of the prisoner from all human society, and his confinement in a cell of considerable size, so arranged that he had no direct intercourse with or sight of any human being and no employment or instruction….

A considerable number of the prisoners fell, after even a short confinement, into a semi-fatuous condition, from which it was next to impossible to arouse them, and others became violently insane; others still committed suicide, while those who stood the ordeal better were not generally reformed, and in most cases did not recover sufficient mental activity to be of any subsequent service to the community.

It became evident that some changes must be made in the system, and the separate system was originated by the Philadelphia Society for Ameliorating the Miseries of Public Prisons, founded in 1787.

Following the standard journalistic narrative, Dr. Gawande leads with his best anecdote and ends with his second-best. The entire piece is a must read, but the last anecdote is particularly astonishing. Gawande describes the case of Robert Felton, who spent 14 years of his 36 years on earth in solitary confinement. The isolation drove him crazy, Gawande writes, and Felton tried so many times to set his cell on fire with a lightbulb that “the walls of his cell were black with soot.”

Gawande writes about one of his last meetings with Felton. Felton had just found out the prison director who kept him in solitary confinement had just been convicted of bribery (from lobbyists, a sidestory that would probably illuminate why America holds on to certain prison strategies regardless of effect) and sentenced to two years in prison:

“Two years in prison,†Felton marvelled. “He could end up right where I used to be.â€

I asked him, “If he wrote to you, asking if you would release him from solitary, what would you do?â€

Felton didn’t hesitate for a second. “If he wrote to me to let him out, I’d let him out,†he said.

This surprised me. I expected anger, vindictiveness, a desire for retribution. “You’d let him out?†I said.

“I’d let him out,†he said, and he put his fork down to make the point. “I wouldn’t wish solitary confinement on anybody. Not even him.â€