The technical part of this post is painful, but not this painful

Great programmers and thinkers have already railed against Jeff Atwood’s essay, “Please Don’t Learn to Code.”

But we haven’t heard enough from amateurs like me, nor has anyone, as Poynter’s Steve Myers claims, “written a single line of code” in response to Atwood.

Well, I may not be Zed Shaw but I have a knack for coming up with the most brain-numbing code snippets to deal with slightly more brain-numbing journalism-related tasks, such as extracting data from PDFs, scraping websites, producing charts, cropping photos, text processing with regular expressions, etc. etc..

But for this post I’ll try to show (with actual code) how programming can apply even to a field that’s about as far removed from compilers and data-mining that I can think of: fashion design

(insert joke about fat-models and skinny-controllers)

—-

Besides clearance sales at the flagship Macy’s, my main specific connection to the New York fashion industry comes from the few times that a friend of a friend hires me to take photos at a casting call.

I knew there were casting directors in TV and movie business. But I thought designers could just pick for themselves the models. Well, they do. But there’s still need for someone who handles relations with modeling agencies, managing the logistics of bringing in and scheduling hundreds of models, and having the aesthetic sense to make valuable recommendations to the designers.

And, sometimes, there’s the occasional holy-shit-does-anyone-own-a-camera-because-this-came-up-at-the-last-minute scenarios that create the need for non-fashion professionals like me. During the day of the casting call, the director and designers are busy doing informal interviews of the models, skimming their lookbooks, and judging – yes, there seems to be a wide range of skill and style in this – their strut down the catwalk.

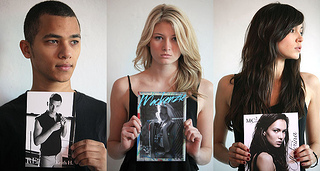

The models don’t show up primped as if it were a Vogue cover shoot, and they probably couldn’t maintain that look over the other 5 to 15 other casting calls they trek to throughout the day. Often, at least to me, they look nothing like they do in their lookbooks. Which is fine since the designers need to imagine whether they’d fit for their own collections.

So I take photos of the models – of the face looking at the camera, then looking off-camera, and then a full-length head-to-heels shot – and then say “thank you, next please.” The photos don’t even have to be great, only recognizable so that the designer and directors have something to refer to later on. It’s likely one of the easiest and most monotonous photo assignments (at least to the point that my brain starts to think about programming), like yearbook photo day at a high school where almost nobody smiles or blinks at the wrong time.

So casting calls are uncomplicated from my extremely limited standpoint. But there are logistical hassles that come into play. A friend of mine who actually does real work in fashion told me, when Polaroid film went out of production, casting directors “pretty much shit themselves.”

For the digital-only generation, Polaroids were great because they printed the photo right after it was taken. Having a physical photo just as the model is standing there made it easy to attach it to the model’s comp card for later reference.

With digital cameras, the photos are piled in a memory card’s folder under a sterile naming convention such as “DSC00023.jpg” and won’t materialize until the memory card is taken out, brought over and inserted into a computer, and then printed out. Unless I’m doing that right after each model, there has to be some system that tracks how “DSC00023.jpg” is a snapshot of “James S.” from Ford Models at the end of the day.

Stepping back from the material world of fashion, this is at its core a classic data problem: in lieu of instant print photography, we need to link one data source, the physical pile of comp cards containing each model’s name, agency, and sometimes measurements – with another – the folder of generically named photo files in my camera.

There’s nothing about the contents of the digital photo file that conclusively ties it to the real-life model and comp card. On a busy casting call, there are enough models to sort through and some of them look similar enough (or different from their comp card) that it’s not obvious which “normal” snapshot goes with the comp card’s highly-produced portrait.

Assuming the photographer hired is too cheap (i.e. me) to invest in wi-fi transmitters and the like, the director can throw old-fashioned human labor at the problem. I once had an assistant with an even more monotonous task than mine: writing down the name of each model and the photo filenames as I read them off my camera. The director has her own assistant who is also writing down the models’ names/info while collecting their cards.

Having the models hold up their comp cards

One way to reduce the chance of error is to have the models hold up their comp cards as I take the snapshots. But no matter how error-free the process is, there’s still the tedious work of eyeballing hundreds of printouts and clipping them to the correct comp cards.

The code fix

Let’s assume that the procession of models is swift and substantial enough (200-500 for New York Fashion Week, depending how many shows the casting director has been hired for) that the chronological order of the physical comp cards and the digital photos is bound to be muddled.

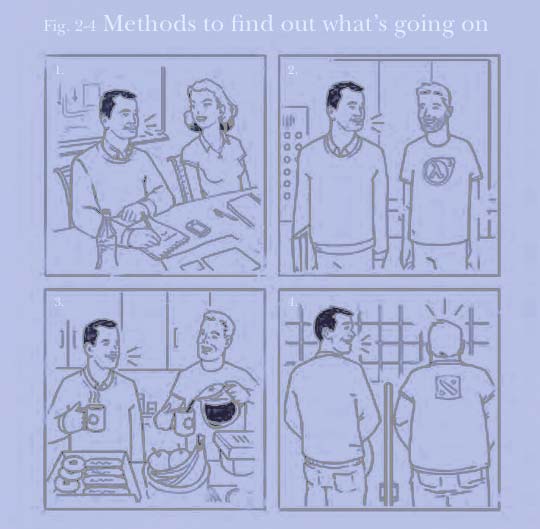

So, in our traditional setup, the linking of the two data sources is done through facial/image recognition:

Casting director: “Hey, can you find me Aaron from Acme’s photos? He has brownish hair, bangs and freckles and I think he came earlier in the day.”

Assistants: “OK!” (they hurriedly look through the pile of photos until someone finds the photo matching the description. The photo could be near the top of the pile or at the bottom for all they know).

The code-minded approach: attach the name and agency information to the digital so there’s a way to organize them. They can, for instance, can be printed out and sorted into piles by agency and in alphabetical order.

Casting director: “Hey, can you find me Aaron from Acme’s photos?

Assistants: “OK!” (someone goes to the Acme pile, which is sorted alphabetically, and looks for “Aaron”).

So how do we get to this sortable, scalable situation without adding undue work, such as having the photographer rename the photos in-camera or printing them out after finishing up with each model? Here’s a possible code solution that efficiently labels the photos correctly long after the model has left the call:

- Have the photographer sync up his camera’s system time with your assistant’s laptop’s time.

- Have the assistant open up Excel or Google Spreadsheets and mark the time that the model has his/her photos taken:

- At the end of the day, tell the photographer to dump the photos into a folder, e.g. “/Photos/fashion-shoot”

| Name | Agency | Time |

| Sara | Acme | 9:10:39 AM |

| Svetlana | Acme | 9:12:10 AM |

| James | Ford | 9:15:57 AM |

And then finally, run some code. Here’s the basic thought process:

- Each line represents a model, his/her agency, and their sign-in time

- For each each line of the spreadsheet:

- Read the sign-in time of that line and the sign-in time of the next

- Filter the photofiles created after the sign-in time of the given model and before the sign-in time of the next model

- Rename the files from “DSC00010.jpg” to a format such as: “Anna–Acme Models–01.jpg”

If you actually care, here’s some Ruby code, which is way more lines than is needed (I’ve written a condensed version beneath it) because I separate the steps for readability. I also haven’t run it yet so there may be a careless typo. Who cares, the exact code is not the point but feel free to send in corrections.

# include the Ruby library needed to

# turn "9:12:30 AM" into a Ruby Time object

require 'time'

# Grab an array of filenames from the directory of photos

photo_names = Dir.glob("/Photos/fashion-shoot/*.*")

# open the spreadsheet file (export the XLS to tab-delimited)

spreadsheet_file = open("spreadsheet.txt")

# read each line (i.e. row) into an array

array_of lines = spreadsheet_file.readlines

# split each line by tab-character, which effectively creates

# an array of arrays, e.g.

# [

# ["Sara", "Acme", "9:10:39 AM"],

# ["James", "Ford", "9:15:57 AM"]

# ]

lines = lines.map{ |line| line.chomp.split("\t") }[1..-1]

# (the above steps could all be one line, BTW)

# iterate through each line

lines.each_with_index do |line, line_number|

# first photo timestamp (convert to a Time object)

begin_time = Time.parse(line[2])

# if the current line is the last line, then we just need the photos

# that were last modified (i.e. created at) **after** the begin_time

if line_number >= lines.length

models_photos = photo_names.select{|pf| File.mtime(pf) >= begin_time }

else

# otherwise, we need to limit the photo selection to files that came

# before after the begin_time of the **next row**

end_time = Time.parse(lines[line_number + 1])

models_photos = photo_names.select{ |pf| File.mtime(pf) >=

begin_time && File.mtime(pf) < end_time }

end

# now loop through each photo that met the criteria and rename them

# model_name consists of the name and agency (the first two columns)

model_name = line[0] + "--" + line[1]

models_photos.each_with_index do |photo_fname, photo_number|

new_photo_name = File.join( File.dirname(photo_fname),

"#{model_name}--#{photo_number}.jpg" )

# you should probably create a copy of the file rather

# than renaming the original...

File.rename(photo_fname, new_photo_name)

end

end

Here's a concise version of the code:

require 'time'

photo_names = Dir.glob("/Photos/fashion-shoot/*.*")

lines = open("spreadsheet.txt").readlines.map{ |line| line.chomp.split("\t") }[1..-1]

lines.each_with_index do |line, line_number|

begin_time = Time.parse(line[2])

end_time = line_number >= lines.length ? Time.now : Time.parse(lines[line_number + 1])

photo_names.select{ |pf| File.mtime(pf) >= begin_time &&

File.mtime(pf) < end_time }.each_with_index do |photo_fname, photo_number|

new_photo_name = File.join( File.dirname(photo_fname),

"#{line[0]}--#{line[1]}--#{photo_number}.jpg" )

File.rename(photo_fname, new_photo_name)

end

end

The end result is a directory of photos renamed from the camera's default (something like DSC00026.jpg) to something more useful at a glance, such as Sara-Acme-1.jpg, Sara-Acme-2.jpg and so forth. The filenames are printed out with the images.

So even if the physical comp cards are all out of chronological order, it's trivial to match them alphabetically (by name and agency) to the digital photo print outs. As a bonus, if someone is taking videos of each model's walk on a phone and dumps those files into the photo directory, those files would also be associated to the model (this might require a little more logic given the discrepancy between the photo shoot and catwalk test).

With a few trivial modifications to the code, a coding-casting director can make life even easier:

- Add a Yes/No column to the spreadsheet. You'd either enter this value in yourself or give some kind of signal to your assistant (ideally more subtle than "thumbs up/thumbs down" while the model is still standing there). And so you could save yourself the trouble of printing photos of the non-viable candidates.

- Why even use a printer? Produce a webpage layout of the photos (add a few lines that print HTML: "<img src='Sara-Acme-1.jpg'>")

- If the client is old-style and wants the photos in hand as she marks them up and makes the artistic decision of which model would look best for which outfit, then you can at least resize and concatenate the photos with some simple ImageMagick code so that they print out on a single sheet (like in a photo booth), reducing your printing paper and ink costs. Congratulations, you just saved fashion and the Earth.

- If you hire a cheapo photographer (like myself) who didn't buy/bring the lighting equipment/batteries needed to keep consistent lighting as the daylight fades, then models who show up at the end of the call will be more lit up (and probably more reddish) by artificial lightings. A line of code could automatically adjust the white balance (maybe by executing a PhotoShop action) depending on the timestamp of the photo.

- Fashion bloggers: speaking of color adjustments, you can get in on this programmatic color-detecting action too: if your typical work consists of curating photos of outfits/accessories that you like, but you've done a terrible job taking the time to tag them properly, then you can use ImageMagick to determine the dominant hue (probably in the middle of the photo) and auto-edit the metadata. Now you can create pages that display fashion items by color and so with no manual labor and fairly easy coding work on your part, your readers have an extra reason to stay on your site.

A model has her face photographed, from a casting call during NY Fashion Week Spring 2012.

Forget the details, though. The important point is that someone with code can abstract out the steps of this chore and – just as importantly – expedite them without adding work. They see how to exploit what already has to be collected (photos, names) and use what is essentially useless to non-coders (file timestamps, metadata). And, thanks to the speed of computing, the menial parts of the job are reduced, allowing more time and energy for the "fun", creative part.

Of course the number of times I've offered to do this for a director (or any similar photojob) is zero. It's not the code-writing that's hard. It's understanding all the director's needs and processes and explaining to and getting everyone to follow even the minimal steps outlined above. It's much easier for me to just stick to my role of bringing a camera and pressing its button a thousand or so times. The incentive to implement this pedantic but life-improving code rests within the person whose happiness and livelihood is directly related to the number of hours spent pointlessly sifting papers.

But since casting calls have gone fine for directors without resorting to this fancy code thing – or else they would no longer be casting directors – why fix what's not yet broken, right?

Jeff Atwood writes, "Don't celebrate the creation of code, celebrate the creation of solutions." In other words, focus on what you do best and let the experts handle the code. But the problem is not that non-coders can't create these solutions themselves. The problem is that they don't even know these solutions exist or why they are needed.

They suffer from, as Donald Rumsfeld described best, the "things we do not know we don't know." But so do those on the other side of the equation; expert coders really don't grasp the innumerable and varied obstacles facing non-coders. So isn't it a little premature to dismiss the potential of a more code-literate world?

It's a bit like the church, soon after Gutenberg's breakthrough, telling everyone: Hey, why waste your already-short lives trying to become literate? It's hard work; we know, because our monks and clerics devote their entire lives to it. So even if you do learn to read, you're likely to make some uneducated, sacrilegious misinterpretation of our holy texts and spend the afterlife in eternal damnation. So all you need to know is that books contain valuable information and that we have experts who can extract and interpret that information for you. That's what we've done for centuries and things have gone very well so far, right?

I don't mean at all to imply that Atwood wants to keep knowledge from the masses. But I do think he vastly underestimates the gulf of conceptual grasp between a non-programmer and even a first-year programmer. And he undervalues the potential (and necessity, IMHO) of programming to teach these abstract concepts.

Erik Hinton from the New York Times puts it nicely:

If you don't know how to program, you filter out all parts of the world that involve programming. You miss the loops and divide-and-conquers of everyday life. You cannot recognize programming problems without the understanding that outlines these problems against the noise of useless or random information.

Atwood imagines that non-programmers can somehow "get" the base level of data literacy and understanding of abstraction that most programmers take for granted. I'd like to think so, but this is not the case even for professionals far more grounded in logic and data than is the fashion world, including researchers, scientists, and doctors. For instance, check out researcher Neil Saunders's dispatches on attempting to introduce code and its wide-scale benefits to the world of bioinformatics.

My New Year's resolution is to learn to code with Codecademy in 2012! Join me. codeyear.com #codeyear

— Mike Bloomberg (@MikeBloomberg) January 5, 2012

So I too am skeptical that Mayor Bloomberg, despite his resolution to learn to code, will ever get around to creating even the classic beginners customer-cart Rails app. But perhaps his enthusiasm will trickle down to whoever's job it is to realize that maybe, the world's greatest city just might be able to find a better way to inform its citizens about how safe they are than through weekly uploads of individual PDF files (Or maybe not. Related: see this workaround from ScraperWiki).

My own journalism career benefits from being able to convert PDFs to data at a rate/accuracy equivalent to at least five or more interns. But I'd gladly trade that edge for a world in which such contrived barriers were never conceived. We don't need a bureaucrat who can install gcc. I'll settle for one who remembers enough about for loops and delimiters and can look a vendor in the eye and say, "Thank you for demonstrating your polished and proprietary Flash-powered animated chart/export-to-PDF plugin, which we will strongly consider during a stronger budget year. But if you could just leave the data in a tab-delimited text file, my technicians can take care of it."

I do share some of Atwood's disdain that the current wave of interest in coding seems to be more about how "cool" it is rather than something requiring real discipline. So don't think of coding as cool because that implies that you are (extremely) uncool when you inevitably fail hard and fast at it in the beginning. Focus instead on what's already cool in your life and work and see how code can be, as Zed Shaw puts it, your secret weapon.

How can coding help non-professional programmers? I've already mentioned Neil Saunders in bioinformatics; here are a few others that came from the Hacker News discussion in response to Atwood: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Finding this purpose for programming may not be obvious at first. But hey, it exists even for fashion professionals.

-----

Some resources: I think Codecademy is great for at least getting past the technical barriers (i.e. setting up your computer's development environment) to try out some code. But you'll need further study, and Zed Shaw's Learn Code the Hard Way is an overwhelmingly popular (and free) choice. There's also the whimsical why's poignant guide to Ruby. And I'm still on my first draft of the Bastards Book of Ruby, which attempts to teach code through practical projects.

Using dummy data — and forgetting to remove it — is a pretty common and unfortunate occurrence in software development…and in journalism (

Using dummy data — and forgetting to remove it — is a pretty common and unfortunate occurrence in software development…and in journalism (