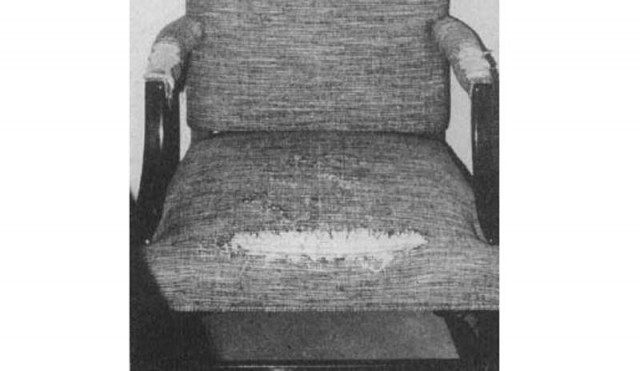

A chair with its front worn out: image cropped from Sapolsky's book, Why Zebras Don't Get Ulcers, Third Edition

Sometimes the great insights about how things really work can come from the people who are thought to be too far down the ladder to possibly understand the big picture. Robert M. Sapolsky, an author and professor of neurology at Stanford, coined a proverb for this phenomenon:

“If you want to know if the elephant at the zoo has a stomachache, don’t ask the veterinarian, ask the cage cleaner.â€

In other words, the low-level employees who fix what’s broken may often be in the best position to first notice when, why, and how something broke. Or, as Sapolsky puts it: “People who clean up messes become attuned to circumstances that change the amount of mess there is.”

This is not just a cute aphorism to remind you to tip your cleaning lady, but a lesson that has manifested itself at least a few times in scientific history. Sapolsky retells the confession of Dr. Meyer Friedman, who – with his partner R. H. Rosenman – is credited with discovering the link between Type-A personalities and heart disease. This revelation sparked off the field of research into how physical and mental health are intertwined.

According to Friedman, though, the breakthrough observation first came from his upholsterer:

It was the mid-1950s, Friedman and Rosenman had their successful cardiology practice, and they were having an unexpected problem. They were spending a fortune having to reupholster the chairs in their waiting rooms. This is not the sort of issue that would demand a cardiologist’s attention. Nonetheless, there seemed to be no end of chairs that had to be fixed. One day, a new upholsterer came in to see to the problem, took one look at the chairs, and discovered the Type A-cardiovascular disease link.

“What the hell is wrong with your patients? People don’t wear out chairs this way.†It was only the front-most few inches of the seat cushion and of the padded armrests that were torn to shreds, as if some very short beavers spent each night in the office craning their necks to savage the fronts of the chairs. The patients in the waiting rooms all habitually sat on the edges of their seats, fidgeting, clawing away at the armrests.

The rest should have been history: up-swelling of music as the upholsterer is seized by the arms and held in a penetrating gaze—“Good heavens, man, do you realize what you’ve just said?†Hurried conferences between the upholsterer and other cardiologists. Frenzied sleepless nights as teams of idealistic young upholsterers spread across the land, carrying the news of their discovery back to Upholstery/Cardiology Headquarters—“Nope, you don’t see that wear pattern in the waiting-room chairs of the urologists, or the neurologists, or the oncologists, or the podiatrists, just the cardiologists. There’s something different about people who wind up with heart diseaseâ€â€”and the field of Type-A therapy takes off.

Unfortunately for the upholsterer, Dr. Friedman was too busy to listen to him. Only years later, when Friedman and Rosenman conducted studies of their patients did Friedman finally grasp the importance of what his upholsterer had discovered (although not the upholsterer’s name).

It’s hard to know how many other “Eureka, the janitor is right!” moments that science and technology are beholden to. Unlike the case of Sir Alexander Fleming, it’s one thing to say how, out of genius and keen observation, you made lemonade out of lemons (in Fleming’s case, penicillin after forgetting to put away his staph samples during summer vacation). It’s a little more deflating to admit that the maintenance worker beat you to the discovery.

Cleaning up the mess in online advertising

Eric Veach, who author Steven Levy describes as the “Google engineer who created the most successful ad system in history,” was no mere low-level grunt when he designed the implementation for AdWords (although apparently, this accomplishment isn’t enough to inspire someone to write a Wikipedia entry on him). He came to Google in 2000 after working on Pixar’s movie-rendering software and was assigned to the ad department, which Veach describes to Levy as “a backwater of the company.” (Levy, Steven (2011-04-12). In The Plex p. 83.)

At that time, Google ads were still sold by actual people and Google had declined an offer to merge with Overture Services, then the leader in auction-bid online advertising and later acquired by Yahoo. So Veach was part of the team to create Google’s own auction system. Veach had observed – and strongly disliked – how Overture’s system invited a kind of “cat-and-mouse game” between bidders: If the winning bidder bid $100, it would have to pay $100, even if the next bidder had only bid $50. The optimal strategy, of course, was to bid the lowest increment possible to edge out the other bidders, which led to the use of automated software to game the system.

This was not an ideal competitive situation. And, according to other reports, Veach and Salar Kamangar were dismayed at its impact on server load, since advertisers would frequently log in to make these minor bid modifications. To clean up this mess, Veach designed a different model. As Levy describes it:

The winner of the auction wouldn’t be charged for the amount of his victorious bid but instead would pay a penny more than the runner-up bid. (Example: If Joe bids 10 cents a click, Alice bids 6, and Sue bids 2, Joe wins the top slot and pays 7. Alice is in the next slot, paying 3.) It was incredibly liberating because it eliminated the fear of “winner’s remorse,†where the high bidder in an auction feels suckered by paying too much.

Levy, Steven (2011-04-12). In The Plex (p. 90). Simon & Schuster, Inc.. Kindle Edition.

Veach’s model was so counter-intuitive that he had to constantly defend it, even to Larry Page and Sergey Brin. He was vindicated when AdWords (which had several other technical innovations behind it) went on to help Google to its first profitable year in 2002.

As Levy writes, Veach’s method had already been vouched for, in high places:

Part of her [Sheryl Sandberg, former chief of staff to the secretary of the treasury in the Clinton administration] job at Google was explaining its innovative auction. She kept staring at the formula, wondering why it seemed so familiar. So she called her former boss, Treasury Secretary Larry Summers. “Larry, we have this problem,†she said. “I’m trying to explain how our auction works—it seems familiar to me.†She described it to him. “Oh yeah,†said Summers. “That’s a Vickery second-bid auction!†He explained that not only was this a technique used by the government to sell Federal Reserve bonds but the economist who had devised it had won a Nobel Prize.

Veach had reinvented it from scratch.

Levy, Steven (2011-04-12). In The Plex (p. 90). Simon & Schuster, Inc.

While Veach was not some low-level “cage cleaner,” his job did involve cleaning up a seedy part in the world of online advertising. Levy’s book may gloss over whatever mathematical proofs and logic Veach used in deciding on the second-bid auction method. But given that Veach’s strategy was initially doubted by Google’s founders, who themselves were not shy to contrarian thinking, Veach is a good example of how those who get their hands dirty may end up with a clearer “big picture” of how a system truly works.

The pre-mortem

The case of Friedman’s upholsterer is by definition, a rare occurrence. A more common – and tragically so – kind of cage-cleaner is the whistleblower.

Dr. Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize-winning quantum physicist, might be best remembered by the general public for his role in the investigation of the Challenger disaster. During a televised press conference, Feynman used a cup of ice water to demonstrate how NASA’s managers apparently overlooked a simple tenet of physics that helped lead to the shuttle explosion:

But as Dr. Feynman tells in the second half of his book, What Do You Care What Other People Think? (which should be required reading for all scientists, engineers, and journalists), he may have gotten credit for the revelation of the shuttle’s O-ring, but he did not come up with it himself. One of his fellow commission members pointed out the possible defect to him. And that commission member had been told about it by an anonymous astronaut, who said that NASA had data demonstrating the O-ring’s problem but apparently hadn’t used it.

The truism that “Hindsight is 20/20″ is sometimes used to excuse the most boneheaded of screw-ups. It’s not that it took the Challenger to blow up before we could discover that the O-rings, like most other solids in existence, lose resilience when it’s cold out. High-level managers had the information available to them; they just chose to overlook the complaints and observations of low-level engineers. The good-natured Feynman was so alarmed by NASA’s “fantastic faith in the machinery” that he threatened to quit the investigation unless they included his criticisms in the final report.

But anyone who works in an organization of more than 2 people can attest to how fear of being ostracized can make it difficult to stop a project or plan in motion. During a Let’s-Go!-type of team meeting, there’s nothing more of a buzz-kill than someone in the back constantly complaining how the i’s aren’t all properly dotted.

In his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” psychologist Daniel Kahneman (a Nobel Prize winner himself) describes how psychologist Gary Klein devised a sort of “partial remedy” that I had never heard of before – but that I wish were more commonplace: the “premortem“:

The procedure is simple: when the organization has almost come to an important decision but has not formally committed itself, Klein proposes gathering for a brief session a group of individuals who are knowledgeable about the decision. The premise of the session is a short speech: “Imagine that we are a year into the future. We implemented the plan as it now exists. The outcome was a disaster. Please take 5 to 10 minutes to write a brief history of that disaster.â€

The premortem has two main advantages: it overcomes the groupthink that affects many teams once a decision appears to have been made, and it unleashes the imagination of knowledgeable individuals in a much-needed direction. As a team converges on a decision—and especially when the leader tips her hand—public doubts about the wisdom of the planned move are gradually suppressed and eventually come to be treated as evidence of flawed loyalty to the team and its leaders. The suppression of doubt contributes to overconfidence in a group where only supporters of the decision have a voice. The main virtue of the premortem is that it legitimizes doubts. Furthermore, it encourages even supporters of the decision to search for possible threats that they had not considered earlier.

Kahneman, Daniel (2011-10-25). Thinking, Fast and Slow (pp. 264-266). Macmillan.

Just like the egotistical scientist who is loathe to give credit to a janitor for first making a groundbreaking observation, no project manager likes admitting that disaster was averted only through the foresight of an underling. The problem is such that in bureaucracies, managers may actively avoid receiving such momentum-killing feedback, and underlings who wish to keep their jobs may lean toward keeping quiet rather than being pegged as the negative nancy.

The pre-mortem, which (ideally) rewards contributors for thinking destructively, may be one of the few ways to recognize the cage-cleaners who deal with the muck. Or at least, the people who take the time to listen to them.

Pingback: Valve’s New Employees Handbook: “What is Valve *Not* Good At?” | Dan Nguyen pronounced fast is danwin